The Capitalist Guide to Killing Free Webtech

The tech elite are professional vandals. If it's worth more broken than it's worth in a functional state, then inevitably, those with the power to do so will make sure it gets broken. But there's a special art to breaking the supposedly everlasting free and open source branch of webtech.

Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) is so often pitched as a solution to the destructive effects of capitalism in the cybertech world. Because, to quote the immortal cliche:

Quote

"If FOSS webtech lapses into a profit-crazed nosedive, someone else can simply fork the project and drag it back onto a positive trajectory, right?"

If only it were that straightforward.

Taking on the maintenance and financial burden of a complex and popular software project is a life-impounding business commitment. It certainly isn't something to which the word "simply" could reasonably be applied. And most often, there is no "someone else". No casual code-dabbler is going to dedicate their foreseeable life and X million quid of borrowed money to the accommodation of other people's frivolous, ungrateful consumerist gluttony, with no payback horizon.

So in reality, the only people who are going to step in when popular FOSS goes bad, are capitalists - investing and expecting their own reward. Which just reboots the same cycle that drove the software to destruction in the first place.

But for the public, there's still another theoretical workaround on the table when capitalism ransacks FOSS.

Rewind. Turn back the clock.

Simply (there's that word again) use a version of the software that was made before the rot set in. I mean, the licensing of FOSS ensures that once it's been released, it can't be retracted. So, surely, capitalism can't cut off that escape route. Can it?...

In this post I'll take you behind the scenes for a developer's-eye view of the destructive forces within FOSS, working to ensure that even Libre software is persistently rendered useless when it treads on capitalism's toes.

A REAL-LIFE FOSS STORY

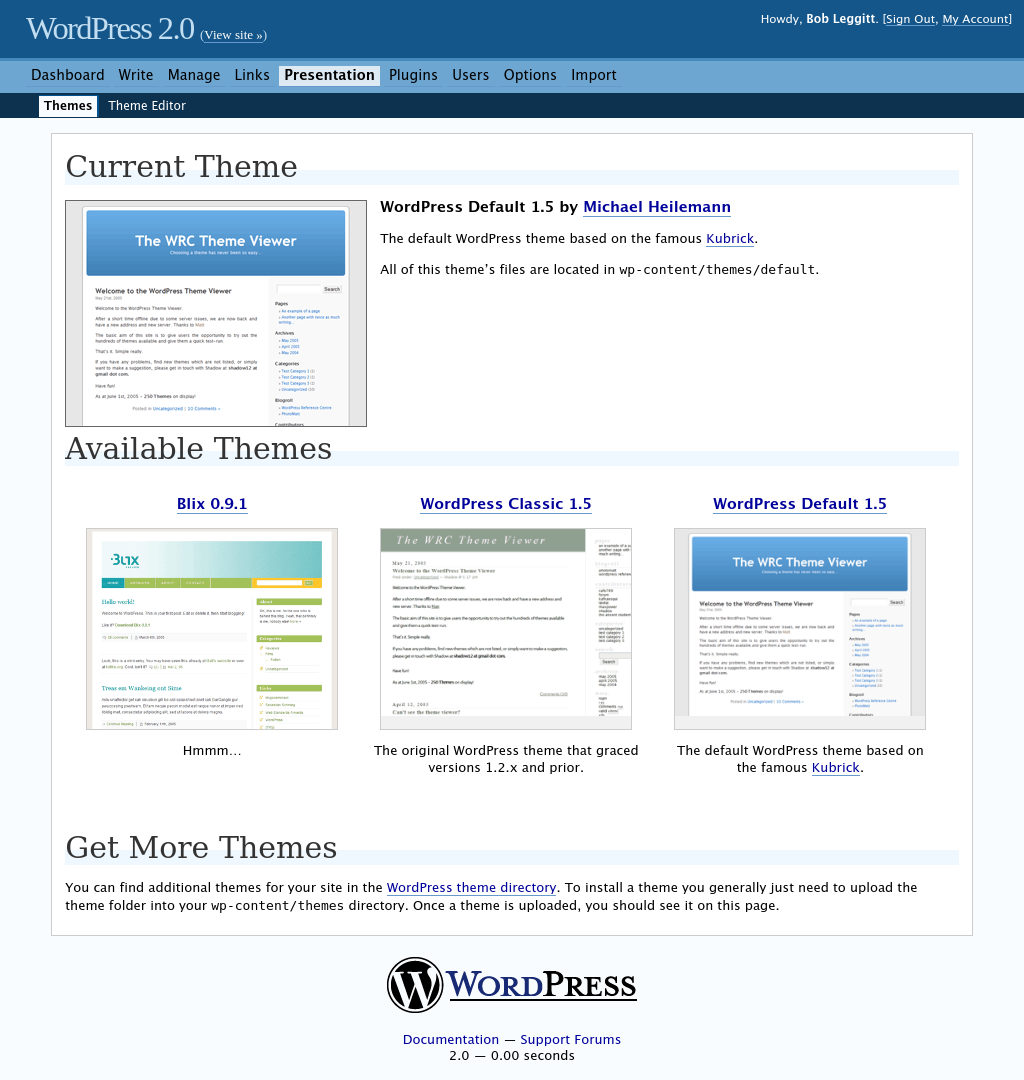

Last year I worked through a fascinating investigative project plotting the performance and user experience offered by different WordPress versions, from the first beta - an immediate descendant of the deep indie creation b2 - to the recent e-commerce behemoths.

What a contrast I saw. The spring 2003 WordPress beta was little more than a re-skinned fork of an existing, cult-followed blogging package - very indie, very spartan, very fast.

In stark contradiction to that, recent versions of WordPress are slow, bloated and confusing. Their site-building tools are so excruciatingly cumbersome and restrictive that it's actually easier to knock up a decent home page using a code-based developer library.

The obvious solution to this problem is to install an old version of WordPress, restoring all of the sharpness, convenience and speed of days gone by. I mean, we can do that, right? Actually, no, we can't. And you're now going to see why. I'll show you how "non-current" webtech is being broken on a continuous basis. You'll see how easy it is for the Web's Fat Controllers to kill off older webtech installations - without even touching the releases themselves.

If the tech industry were a local tyre-fitting garage, its method of "marketing" would be to belt-sand the tread off five hundred tyres per week, then adorn each with an "End of Life" sticker and the garage's phone number.

WHY BREAK WEBTECH?

It's now pretty widely recognised that when you use most cyber technology, you're not the customer - you're the product. Even if you're paying. Still the product. The idea is not to court you with better and better features. It's to bait you, trap you, farm you and sell you. In the early stages of that sequence, the software has to be good. It's neither going to bait you nor trap you if it's bad. But in the latter stages, the software needs to start extracting labour, data and other forms of collateral from you. That means the software's user experience will inevitably plummet.

This is the default business model in the cybertech world. But it comes with a fundamental problem for the provider. If you, the user, can still access and use the original implementation of the software, which was designed to bait you, you will inevitably use it in preference to the current implementation of the software, which is designed to farm and sell you. Therefore, the software provider has to find a way to disable your access to the original implementation, so you can't just sub in the good for the bad.

CLASSIC DESTRUCTION STRATEGIES

Forced updates have surfaced as a common means to artificially terminate the life of perfectly usable software, and SaaS (Software as a Service) has established itself as a default supply system. With SaaS, the user has no access to the software itself. Only access to its output, remotely, with the provider controlling the server on which the software is located.

As well as ensuring that old versions can be binned to order, the SaaS setup means that even if the software creator has published the source for what they built, the active software can never qualify as open source. As soon as you put a wall between the user and the provider, any published source code ceases to be the build, and becomes merely a build. There's nothing to stop a SaaS provider from subbing in their own mods behind the scenes, so the actual source code is unknown, and therefore cannot be considered "published".

Even in the world of open source we've been conditioned to accept planned and dated obsolescence as normal. But we should understand that it's not a natural process. It's invariably a capitalist hijack of the altruism that runs through the FOSS developer community.

DESTRUCTION BY PROXY?

But WordPress - at least when it's self-hosted - is different. The code is categorically published, irretractable, and verfiably unmanipulated. In an industry where destruction has for long been a business model, this proved a serious inconvenience for WordPress provider Automattic. WordPress built its brand around Free Software - the most resilient, hardcore-licensed variant of open source available. And as such, Automattic found itself facing a predicament. As a commercial tech enterprise monetising the user as a product, it developed an incentive to stop people from accessing old software versions. But those old versions were readily and persistently available to the public.

You can go and download WordPress 1.0, for free, right now. But you won't be able to use it. And that's the central focus of this article.

Q. How do you break a piece of webtech without withdrawing its availability, or in any way touching its code?

A. You break one or more of its dependencies.

Q. How do you break its dependencies when you don't own them?

A. You, or one of your associates, pay the maintainers of the dependencies to break them on your behalf.

And with that, we'll switch our attention to a programming language called PHP, which became the bedrock of WordPress, and its predecessor b2, from the outset. PHP is server-resident software. It has to be pre-installed for WordPress to install and run. It's a critical WP dependency. And over the years, PHP has relentlessly been broken, with the result that past versions of WordPress catastrophically fail. We're not talking about buggy performance with a few error messages. We're talking instant crash, white screen of death, zero output, 100% useless.

Interestingly, PHP's primary funder just happens to be Automattic - provider of WordPress. I'll leave you to draw the ultimate conclusion on the significance of that, once we finish our exploration.

UNBREAKING THE WEB

In order to enact my tour through WordPress history, I had to somehow "unbreak" a collection of old versions which, because of the persistent, destructive updates to server software over the years, would not work or install on a modern server.

But I was surprised at how trivial the process of unbreaking this decades-old webtech actually was.

And as I began to "unbreak" various old versions of WordPress, along with their majestic 2001/2002 predecessor b2, I asked myself why on Earth they ever needed to become "incompatible" with a current server in the first place. Incompatibility doesn't just happen. People make it happen. The question is: who?

The only thing that should be deprecated in software development is deprecation itself.

BREAKAGE COMPARISON SITE

Once you start to investigate the progressive breakage of webtech, you quickly notice that different programming languages break at very different rates. In fact, some types of old webtech are barely affected by breakage at all. Which suggests that where breakage does continually occur, it's contrived. Organised.

About a decade before WordPress launched, the seeds of what came to be known as back-end web development were sown. With the 1993 introduction of the Common Gateway Interface (or CGI, as it's otherwise known), it was possible for the first time to write interactive computer programs that would run when accessed via a web browser. CGI was not a programming language. It was a facilitator, which allowed the developer to select a programming language of their own choice.

So with CGI set up, you could write an interactive back end for a website in C, or in Pascal, or in Perl, or in Python, etc. If you've delved into 1990s webtech, you'll have seen CGI deployed at the highest level. The high-profile 'nineties web authoring system FrontPage came set up with CGI directories, which housed pre-compiled programs running on Windows as EXE files.

Microsoft exploited the malleability of CGI to push its part-proprietary ASP framework. But as one might expect, the rapidly rising Google didn't like that. Google instead favoured self-contained server provisions like PHP, which - if widely adopted - would heavily hinder Microsoft's effort to tether webtech to the Windows ecosystem.

With the developer community increasingly taking Google's side (often without consciously realising it even was Google's side), CGI began to lose its footing, and PHP steadily took over as a standalone server-side scripting resort.

This had another benefit to Google and its associates - which happened to include WordPress, even in the first half of the 2000s. If the use of CGI waned, the free choice of languages it had offered would whittle down to a small, standardised "webcrafting" set, which would be much easier for a web giant like Google to co-opt and control than the entire gamut of programming languages. And it certainly appears that since that period in the early 2000s, PHP was bombarded with unnecessary breaking changes at a far more intensive pace than non-web-dedicated languages, which had formerly been harnessed for web scripting, at random, through CGI.

To put this notion to the test, I located an original 1990s CGI demo set on a 1998 compact disc - entirely uncontaminated and in its original form. Unlike a WordPress version from as recent as 2019, every single one of the old CGI demos, untouched since the 'nineties, worked with a recent version of their chosen language, on a current server.

This set me thinking...

If not all programming languages break at the same rate, what, exactly, does break, and what doesn't? And most importantly, why the discrepancy?

I quickly realised that front-end Web development languages (the ones that execute in a browser rather than on a server) don't break; whereas dedicated and recognised back-end Web development languages (the ones that run on a standard server without a CGI translation layer) break on a persistent loop. Hmmm...

HTML - the original front-end Web-programming language, is supported with full backward-compatibility. So if you load a 1996 Web page in a new browser, the page will render. A new browser will also render a decades-old chunk of CSS code. And whilst old JavaScript was more fragmented in its implementation from browser to browser, JavaScript that worked in Firefox two decades ago will generally still work in Firefox today. Whilst there are exceptions, it's fair to say that these front-end languages are maintained in a way that preserves as much old functionality as possible.

One definitely cannot say that for something like PHP - the most widely-recognised and widely-used back-end language. PHP, which has driven WordPress from the back since 2003, has endlessly shipped destructive, needless changes and removals of commands.

"The obsessive and endless removal of PHP commands runs way beyond necessity, and appears to come at the whim of higher powers.

HOW PHP BREAKS OLD WORDPRESS VERSIONS

I want to keep this article accessible to all, and that means avoiding code as much as possible. But everyone should see exactly how flippantly and needlessly PHP has been perpetually broken.

For an example, let's zip back to the era of WordPress 0.71, which was created in 2003 using an early version 4 series variant of the PHP scripting language.

Back in the early 2000s when PHP 4.0.6 was current, its pre-defined "superglobal" variables included the following:

$HTTP_GET_VARS

$HTTP_POST_VARS

$HTTP_SERVER_VARS

$HTTP_COOKIE_VARS

You don't need to know what those computer instructions actually did. You just need to know that they had those names.

Then you need to know that the names of the instructions were fairly swiftly changed to:

$_GET

$_POST

$_SERVER

$_COOKIE

Okay, so that's a little easier for a developer to type. But it BREAKS EVERY PIECE OF CODE THAT WAS WRITTEN BEFORE THE CHANGE. Everything containing any of the former commands - even just one of them - stops working. Blank screen. No output. That is how easy it is to break a whole generation of webtech. Remove a few commands from the programming language. Break any and all software that depends on those commands.

I expect a good few people are ahead of me here, and are already asking the obvious question:

"Well, why can't they just introduce the new commands as shortcodes, and retain the old commands?"

Answer: They can. A vast array of programming languages and libraries have done exactly that. And the aforementioned front-end languages - the ones that don't break - they retain obsolete commands too.

When people are told that software has become incompatible, they imagine some incredibly technical revolution of circumstance that makes old software somehow scientifically incapable of living on. But nope, in PHP's case at least, it is literally just people deleting commands from the languagebase.

PHP first "deprecates" the old commands, then developers get a warning not to use them anymore, and are advised of new commands, which will replace them. Then the old commands are removed from PHP, breaking any software that used them.

Meanwhile, at Automattic, WordPress simply switches the old PHP commands for the new ones, which do the same thing as the old ones, then bundles up a new version and releases it. Progressively, as this cycle continues, old versions of WordPress steadily become unusable. Uninstallable, even. It really is no more complicated than that.

Other back-end Web languages have also commonly pulled the rug over the years, but the house of PHP has honed the practice of perpetual breakage into an art form.

IS THIS SABOTAGE? IS IT A CONSPIRACY?

We first need to ask the question:

Why are back-end Web dev languages so prone to persistent breakage, when front-end Web dev languages generally don't break at all?

This question is so important because:

- Front-end tech proves to us that it's entirely possible to maintain programming languages for decades in a non-destructive fashion. In this light, no one steering the course of the PHP codebase can argue that destructive changes are a necessary part of progress.

- For elite cybertech, the consequences for breaking a front end are very different from the consequences for breaking a back end.

- The Web is one entity, and thus the same powers who will seek to control the front end, will also seek to control the back end. In other words, the reason back-end languages break and front-end languages don't is not that the architects of the back end have different goals from the architects of the front end. They're the same people.

So this is only about Point 2 - the stakes.

CONSEQUENCES

What consequences does elite cybertech suffer when a back end breaks? Basically, none. Web admin cries "Boo-hoo, my site doesn't work", and updates his or her WordPress version, and it works again. The back end is controlled by one person or a relatively small group, all of whom passionately care whether or not that specific site works, and will inevitably do what's necessary to make it work.

If HTML, CSS and JavaScript had been broken with the aggression and relentlessness that PHP is broken, virtually no web page last updated more than five years ago would still be accessible.

But at the front end it's much more volatile. The front end is ultimately controlled by the mass public, who decide how, and on which type of device they're going access a site. Five million people still browse the Web with Windows XP. Twenty-six million people still use Internet Explorer. And if you're surprised by those figures, no, it's not an old article, and I am writing in 2025, and I did check and cross-reference.

Additionally, there are people using all manner of independent browsers, and those numbers appear to be exponentially growing. Use of Linux operating systems - which promote the use of more basic Web access tools - is also on the up. Then you have forked browsers, browser extensions, etc, which can block newer technologies. Forked browsers include everything from Brave, Vivaldi, Librewolf and Mullvad, through Pale Moon, Slimjet and Seamonkey, to Stallman-endorsed forks like A Browser and Icecat.

The public, who control the front end environment, don't react in the same way as a Web admin when a site doesn't work. If they land on your health site, fishing site, bike shop site, or whatever, and it doesn't work for them, they will will not try to fix it, or try to contact you to ask you to fix it. They'll just go elsewhere. That's the difference. Because the controller of the front end environment doesn't care about individual sites in the same way that the controller of the back end environment does, he or she does not have the same tolerances, and therefore cannot be bulldozed into taking the kind of complex technical actions that Web admins will take to keep their sites working.

Remember, also, that the Web admin broadly doesn't know that Visitor X, browsing with W3M, or Visitor Y, blocking JavaScript in K-Meleon, encountered a broken page. The admin only tested in Chrome. So as far as they're concerned, everything is hunky-dory and there's nothing to fix.

The corollary, for the cyber gods, is that if front-end programming languages were to persistently break as back-end languages do, said gods would simply lose a huge pile of monetisable data and a huge pile of cash. Furthermore, they would risk being toppled by indie upstarts and their own old versions, as the public sought to re-establish their access to the ever-increasing raft of inaccessible sites. Realistically, if Google said:

"We iz ditchin' HTML tables in Chrome becuz they iz obsolete."

Brave would immediately chime in with:

"We iz restorin' HTML tables in Brave becuz Google iz binnin' 'em off, and that iz another lump of Google's userbase we can reliably poach.

Result: front-end languages stay backward-compatible.

But does that necessarily mean the back-end language PHP is subject to sabotage?

DESTRUCTION FOR THE SAKE OF DESTRUCTION

Well, not necessarily, but there's some pretty heavy circumstantial evidence that it's being broken to order. Compared with other languages, PHP's regime of lucid destruction is disproportionate. And if you understand code and investigate the history, you can see a lot of that destruction was flippant. Entirely unnecessary. In a lot of cases not even logical. Destruction for the sake of destruction.

The main funders of PHP, who pay the maintainers' wages, include both Automattic - makers of WordPress, and JetBrains - a close, dodgy-as-Hell Google partner, which both on its own behalf, and on behalf of the master, has a lot to gain by breaking old server installations.

Changes to the PHP languagebase have to pass a developer vote before they can be implemented. But we don't know what's said to the PHP language developers privately, and most will not bite the hand that feeds them. And even taking that into account, some developers still vote against and protest the changes anyway.

Here's an extensively-reasoned developer argument against a PHP deprecation, and this is only the tip of a huge political iceberg, in which the continued destruction of existing PHP coding conventions is said to be unnecessary, stupid and even dangerous - by the people who make PHP. Meanwhile, the project management defends the proposals in forum threads like their paycheque depends on it. Which is usually a pretty good indication that their paycheque does depend on it.

Suffice it to say that the PHP project has obsessively deprecated and removed commands and conventions on a default basis of "No one outside of the funding machine asked for this". We obviously can't see the funding machine asking for the Web to be broken. They're not stupid enough to do that in plain sight, or without recruiting shills or installing sockpuppets (same old) to do the bidding for them. But there's nowhere else the requests can be coming from. If they were coming from the outside, we would see them. And we can't. There's nothing there. No one says: "Please make PHP break all my old server software". No one asks for anything to be broken. Except the usual suspects, who profit from it.

Go out and ask a hundred impartial developers:

"Which commands would you like to see removed from PHP?"

Every one of them will give the same answer.

"I don't want any commands to be removed."

Why would they want that? Why would they want to keep being forced to RE-LEARN things they could already do? It is tiring to see the deprecation warnings relentlessly appearing in a dev environment. I don't think I'm much different from other developers, and every time I see those warnings I just think:

"For the love of Jesus H Christ STOP PISSING ABOUT WITH THE LANGUAGE AND LET ME GET SOME WORK DONE!"

So no. Developers don't want that. The only people who do want it are the tech bros who plan to pull a rug, and do not have any other means to disable access to the rug they intend to pull.

CODE LIVES FOREVER - IT HAS NO "END OF LIFE"

I used WordPress as an example in this post, because its life has been defined by a hidden regime of vandalism which most people just consider to be an inevitability. A natural consequence of technological evolution. But it's neither natural nor evolution. It's wilful damage, organised by people who know perfectly well that they are breaking products. And this type of needless, persistent destruction is widespread across the tech genre.

Before the age of webtech, only the Mafia used vandalism as a business model. Now it's apparently legitimate behaviour. And remember, the organisers of this are not just breaking their own old versions. If you've built anything that no longer works because "deprecation", they've broken your property.

Maybe it's time for your local wayward youths to start pleading "end of life" with ref to the paintwork they coat with grafitti or the bus shelters they smash?

Quote

"All magnolia is end of life guv. I was just making sure all the walls got repainted with an up-to-date shade."

- Peckham Taggas

And maybe a legion of media sites can leap to their defence, like they do when tech companies trash a generation of developer investment with one selection of a programming command and a tap on the delete button?... Nah. There's no gravy train. They'll continue to headline street vandalism with "JAIL THESE CRIMINALS!". Funny old world, innit?